Each year, as Ramadan approaches, more than 2 billion Muslims around the world prepare for a month of fasting, prayer and community. But Ramadan does not begin on the same day in all parts of the world.

This year, some countries begin the month of fasting on Thursday, February 19, while others begin it a day earlier. Similarly, at the end of Ramadan, different communities will celebrate Eid on different dates.

The reason for this lies in the nature of the lunar visibility calendar: the new Moon is not always visible everywhere on the same date. The Prophet Muhammad is reported to have said: “Observe fasting by seeing [the crescent] and have breakfast when you see it [the next crescent] – but if the sky is cloudy for you, then complete the number [30 days].”

In modern times, some countries such as Türkiye have implemented calendar reforms, eliminating the law of monthly visual sightings of the crescent. Instead, they are based on predetermined calculations.

However, visually observing the Moon to determine the beginning of the month remains the majority practice of Muslims around the world. Most believe that this should be done by eye.

Therefore, cloud cover can affect the start of the month in different locations, making it an unpredictable calendar. This imbues Moon sighting occasions with a sense of communal wonder, but it can also make the topic surprisingly contentious.

A very British problem

When Muslim immigrants who came to the United Kingdom in the mid-20th century tried to see the new Moon, they often had difficulty, partly because of a very British problem: cloudy weather.

As a result, several mosques and communities would outsource their Moon sightings to different countries. Some followed Morocco, others Turkey or Saudi Arabia. As each country could confirm a first sighting on different days, it meant UK mosques could end up with split dates for Ramadan and Eid.

This has been a source of pain for some in the British Muslim community. For me (Imad), who grew up in London, it meant that my friends at school could start celebrating Eid on a different date to me and my family. I found this quite sad, but I assumed it had to be that way.

That changed when I witnessed the community practice of moon sighting during a family vacation in Cape Town, South Africa. When I saw thousands of Muslims gather on the beach to celebrate the new moon, I asked myself: “Why can’t we do this in the UK?”

When I returned from Cape Town, I founded a Muslim calendar lunar observing astronomy club called the New Crescent Society. Our aim is to find a way to celebrate the sighting of the Moon communally across the UK and develop a viable Islamic lunar calendar here, as they have done in other parts of the world.

Sometimes you can see the Moon in Cardiff but not in Cambridge. Sometimes the sky is clear in London but cloudy in Manchester. Our UK-wide astronomy education programme, Moonsighters Academy, now helps Muslims run their own moon watching groups in their communities.

Emma Alexander, CC BY-SA

The astronomy of lunar visibility.

Each month, the Moon goes from a thin crescent, waxing every night, to gibbous (more than half full) and then full, before waning again to a crescent and disappearing again. This cycle occurs due to the Moon’s orbit around the Earth and lasts 29 and a half days.

The Moon does not create its own light. What we see is reflected sunlight and the same face of the Moon is always facing us. It rotates on its axis at the same rate as it orbits the Earth, a phenomenon called tidal locking.

The precise time at which a certain amount of lunar illumination is first visible from Earth each month depends on geometric physics. At this point, the crescent is so thin that even cameras have difficulty determining it.

But as the Moon moves further away from the Sun in the sky, the crescent slowly becomes thicker as the angle of separation increases. There is now a longer “delay” between sunset and moonset, which also makes the new crescent moon more visible. The best time to see a young crescent moon is about halfway between sunset and moonset, balancing sky brightness with lunar altitude.

Astronomers enjoy the challenge of detecting a very thin crescent Moon when it is less than 24 hours old. But how young can a Moon be that people can see with the naked eye? An established milestone of 15 hours 32 minutes was set by astronomer Stephen James O’Meara, who is also known for first detecting Halley’s Comet upon its return in 1985.

When optical aids such as binoculars are introduced, even younger and thinner crescents can be seen. With the right conditions and technology, it is even possible to obtain images of the Moon at the moment of conjunction, with an age of exactly zero hours. This was first achieved by astrophotographer Thierry Legault in July 2013, using an infrared filter on a telescope that had been “baffled” to block the precariously nearby Sun.

So when do Ramadan and Eid start?

This depends on where in the world you are. In Saudi Arabia, the new Moon was declared on Tuesday, February 17, even though it was only about three hours old at sunset. So for Muslims there (and those following the Saudi example), Ramadan begins on Wednesday, February 18.

In the UK, Europe and North Africa, we are likely to have positive New Moon sightings a day later and begin fasting on Thursday 19 February. Countries further east, such as Australia, will probably see the Moon a day later still and will therefore have their first fast on Friday 20 February.

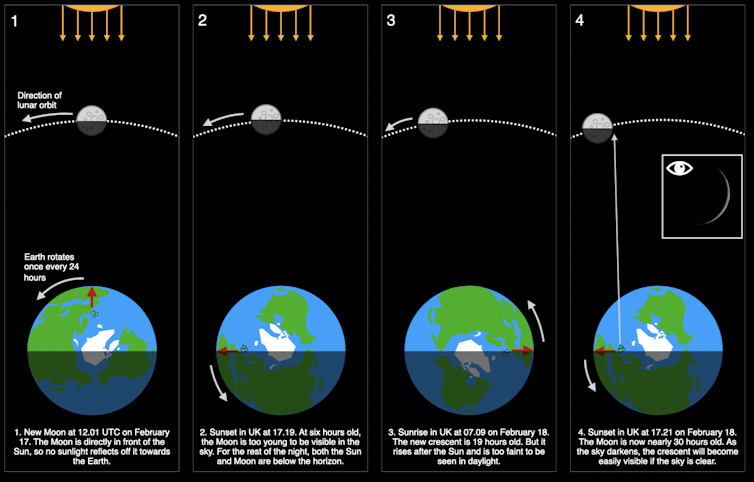

When will the new Moon be visible from the UK (February 17-18):

Emma Alexander, CC BY-SA

Next month, on Thursday March 19, the Moon will be between 17 and 18 hours at sunset, making it difficult – but not impossible – to see it in the United Kingdom, Europe and North Africa. Therefore, we hope that communities following these sightings will begin celebrating Eid on Saturday, March 21. Mosques following Saudi Arabia are likely to celebrate Eid a day earlier.

However, this is not just a story about calendars. When people gather to search the horizon for the crescent Moon, they engage in a practice that links them to the oldest of human practices: observing and connecting with the natural world around them. In Britain, we hope our work can help make this celebration even more unified.